1. Obstruent sounds

A. Definition - an obstruent is a speech sound such as [k], [d͡ʒ], or [f] that is formed by obstructing air flow. Obstruents contrast with sonorants, which have no such obstruction and therefore resonate. All obstruents are consonants, whereas sonorants include vowels and consonants.

B. Obstruent types - obstruents are subdivided into plosives (oral stops), such as [p, t, k, b, d, ɡ], with complete occlusion of the vocal tract, often followed by a release burst; fricatives, such as [f, s, ʃ, x, v, z, ʒ, ɣ], with limited closure, not stopping airflow but making it turbulent; and affricates, which begin with complete occlusion but then release into a fricative-like release. Obstruents are prototypically voiceless, though voiced obstruents are common. This contrasts with sonorants, which are prototypically voiced and only rarely voiceless.

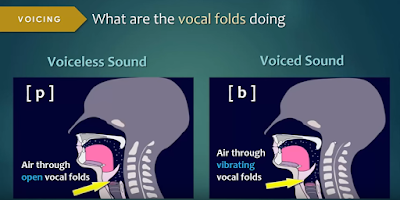

In talking about making air flow into and out of the lungs, the process has been described as though the air was free to pass with no obstruction. But as we saw to make speech sounds we must obstruct the air flow in some way - breathing by itself makes very little sound. We obstruct the airflow by making one or more obstructions or strictures in the vocal tract, and one place where we can make a stricture is in the larynx, by bringing the vocal folds close to each other. Remember that there will be no vocal fold vibration unless the vocal folds are in the correct position and the air below the vocal folds is under enough pressure to be forced through the glottis.

If the vocal folds vibrate we will hear the sound that we call voicing or phonation. There are many different sorts of voicing that we can produce - think of the differences in the quality of your voice between singing, shouting and speaking quietly, or think of the different voices you might use reading a story to young children in which you have to read out what is said by different characters made with the larynx. We can make changes in the vocal folds themselves - they can, for example, be made longer or shorter, more tense or more relaxed or be more or less strongly pressed together. The pressure of the air below the vocal folds (the subglottal pressue) can also be varied.

Three main differences are found:

1. Variations in intensity - we produce voicing with high intensity for shouting, for example, and with low intensity for speaking quietly.

2. Variations in frequency - if the vocal folds vibrate rapidly, the voicing is at high frequency. If there are fewer vibrations per second the frequency is lower.

3. Variations in quality - we can produce different-sounding voice qualities, such as those we might call harsh, breathy, murmured or creaky.

Plosives - a plosive is a consonant articulation with the following characteristics:

- One articulator is moved against another and form a structure that allows no air to escape from one vocal tract.

- After this structure has been formed and air has been compressed behind it, it is released, that is, air is allowed to escape.

- If the air behind the structure is still under pressure when the plosive is released, it is probable that the escape of air will produce noise loud enough to be heard. This noise is called plosion.

- There may be voicing during part or all of the plosive articulation.

English plosives - English has a six plosive consonants, p, t, k, b, d, g. The glottal plosive occurs frequently but it is of less importance, since it is usually just an alternative pronunciation of p, t or k in certain contexts.

The plosives have different places of articulation, p and b are bilabial. The lips are pressed together. t and d are alveolar; the tongue blade is pressed against the alveolar ridge. Normally the tongue does not touch the front teeth as it does in the dental plosives found in many languages. k and g are velar, the back of the tongue is pressed against the area where the hard palate ends and the soft palate begins.

p, t and k are always voiceless. b, d and g are sometimes fully voiced, sometimes partly voiced and sometimes voiceless.

All six plosives can occur at the beginning of a word (initial position), between other sounds (medial position) and at the end of a word (final position). To begin with we will look at plosives preceding vowels (CV, where C stands for a consonant and V stands for a vowel), between vowels (VCV) and following vowels (VC).

- Initial position (CV) - the closure phase for p, t, k and b, d, g takes place silently.

- Medial position (VCV) - the pronunciation of p, t, k and b, d, g in medial position depends to some extent on whether the syllables preceding and following the plosive are stressed. In general we can say that a medial plosive may have the characteristics either of final or of final plosives.

- Final position (VC) - final b, d, g normally have little voicing. If there is voicing, it is at the beginning of the hold phase. p, t, k are, of course, voiceless. The plosion following the release of p, t, k and b, d, g is very weak and often not audible

Fortis and lenis - are b, d, g voiced plosives? The description of them makes it clear that it is not very accurate to call them "voiced". In initial and final position they are scarecly voiced at all, and any voicing they may have seems to have no perceptual importance. Some phoneticians say that p, t, k are produced with more force than b, d, g, and that it would therefore be better to give the two sets of plosives (and some other consonants) names that indicate that fact;

- fortis - so the voiceless plosives p, t, k, are sometimes called fortis (meaning "strong")

- lenis - b, d, g, are then called lenis (meaning "weak")

The plosive phonemes of English can be presented in the form of a table as shown below:

PLACE

OF ARTICULATION

|

|||

bilabial

|

alveolar

|

velar

|

|

FORTIS

(“voiceless”)

|

p

|

t

|

k

|

LENIS

(“voiced”)

|

b

|

d

|

g

|

Tables like this can be produced for all the different consonants. Each major type of consonants (such as plosives like p, t, and k, fricatives like s and z and nasals like m and n) obstructs the airflow in a different way, and these are classed as different manners of articulation.

2. Consonants

A. Definition - In articulatory

phonetics, a consonant is

a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial

closure of the vocal tract. Examples are [p], pronounced with the

lips; [t], pronounced with the front of the tongue; [k], pronounced

with the back of the tongue; [h], pronounced in the

throat; [f] and [s], pronounced by forcing air through a narrow

channel (fricatives); and [m] and [n], which have air

flowing through the nose (nasals). Contrasting

with consonants are vowels.

Terminology - the word consonant comes from Latin stem cōnsonant-, from cōnsonāns (littera) "sounding-together (letter)", Dionysius Thrax calls consonants sýmphōna "pronounced with" because they can only be pronounced with a vowel.

Terminology - the word consonant comes from Latin stem cōnsonant-, from cōnsonāns (littera) "sounding-together (letter)", Dionysius Thrax calls consonants sýmphōna "pronounced with" because they can only be pronounced with a vowel.

Letters - the word consonant is also used to refer to a letter of an alphabet that denotes a consonant sound. The 21 consonant letters in the English alphabet are B, C, D, F, G, H,J, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, X, Z, and usually W and Y. The letter Y stands for the consonant /j/ in yoke, the vowel /ɪ/ in myth, the vowel /i/ in funny, and the diphthong /aɪ/ in my. W always represents a consonant except in combination with a vowel letter, as in growth, raw, and how, and in a few loanwords from Welsh, like crwth or cwm. In some other languages, such as Finnish, y only represents a vowel sound.

Since the

number of possible sounds in all of the world's languages is much greater than

the number of letters in any one alphabet, linguists have

devised systems such as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to

assign a unique and unambiguous symbol to each attested consonant. In fact, the English alphabet has

fewer consonant letters than English has consonant sounds, so digraphs like "ch",

"sh", "th", and "zh" are used to extend the

alphabet, and some letters and digraphs represent more than one consonant. For

example, the sound spelled "th" in "this" is a different

consonant than the "th" sound in "thin". (In the IPA they are

transcribed [ð] and [θ], respectively.)

B. Consonants versus vowels - consonants and vowels correspond to distinct parts of a syllable: The most

sonorous part of the syllable (that is, the part that's easiest to sing),

called the syllabic peak or nucleus, is

typically a vowel, while the less sonorous margins (called the onset and coda) are

typically consonants. Such syllables may be abbreviated CV, V, and CVC, where C

stands for consonant and V stands for vowel. This can be argued to be the only

pattern found in most of the world's languages, and perhaps the primary pattern

in all of them. However, the distinction between consonant and vowel is not

always clear cut: there are syllabic consonants and non-syllabic vowels in many

of the world's languages.

One blurry

area is in segments variously called semivowels, semiconsonants, or glides.

On the one side, there are vowel-like segments that are not in themselves

syllabic but that form diphthongs as part

of the syllable nucleus, as the i in English boil [ˈbɔɪ̯l].

On the other, there are approximants that

behave like consonants in forming onsets but are articulated very much like

vowels, as the y in English yes [ˈjɛs].

The other

problematic area is that of syllabic consonants, segments articulated as

consonants but occupying the nucleus of a syllable. This may be the case for

words such as church in rhotic dialects

of English, although phoneticians differ in whether they consider this to be a

syllabic consonant, /ˈtʃɹ̩tʃ/, or a rhotic vowel, /ˈtʃɝtʃ/: Some

distinguish an approximant /ɹ/ that corresponds to a vowel /ɝ/,

for rural as /ˈɹɝl/ or [ˈɹʷɝːl̩]; others see

these as a single phoneme, /ˈɹɹ̩l/.

Няма коментари:

Публикуване на коментар